‘Bruegel: Defining a Dynasty’ Exhibition, 11 February – 4 June 2017

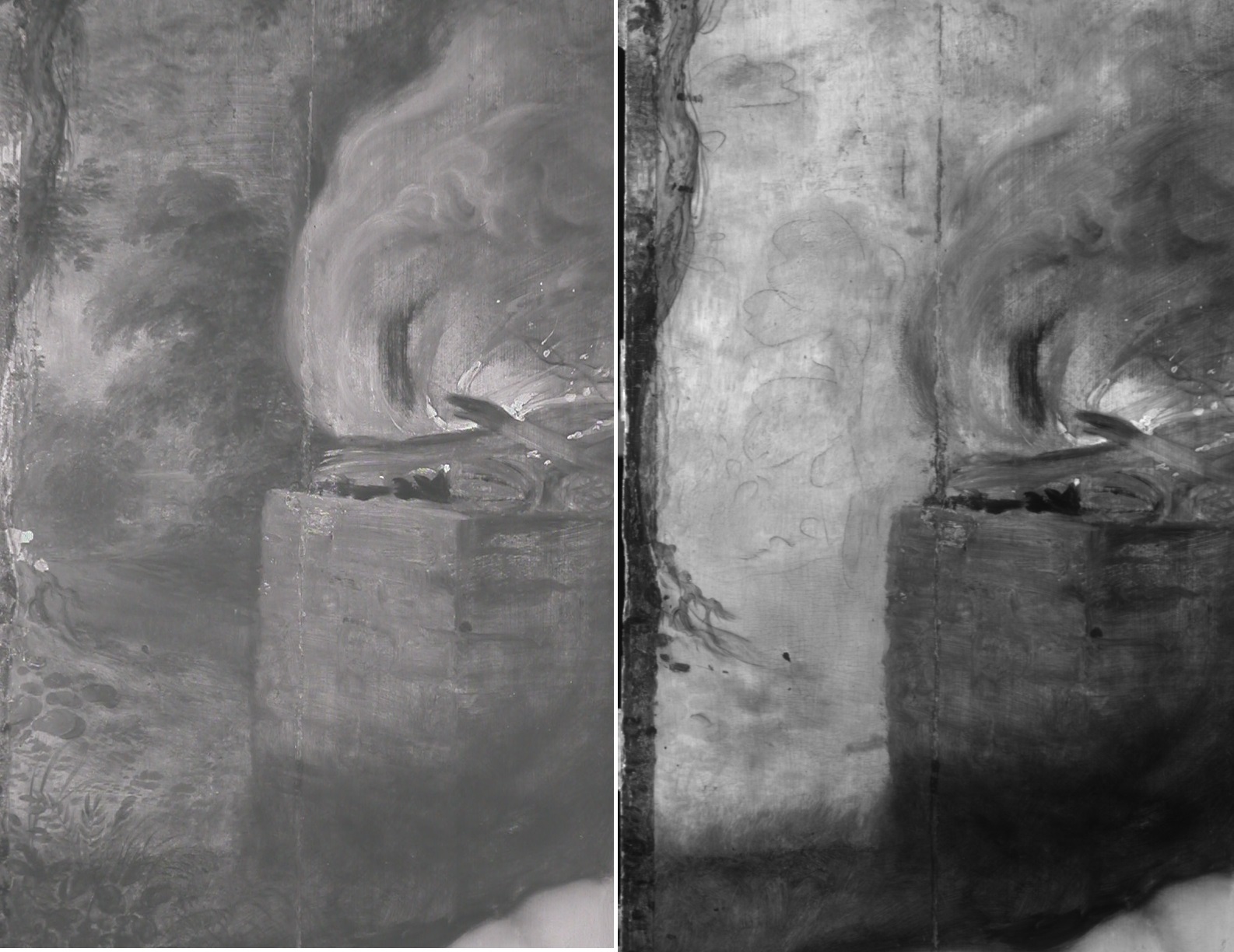

TSR were very excited to undertake infrared examination of the Holburne Museum’s ‘Wedding Dance in the Open Air’. In recent times, much study has been undertaken on paintings based on the compositions of Pieter Bruegel the Elder to try to distinguish his work from that of his sons, Pieter Brueghel the Younger and Jan Brueghel the Elder, their studios and later pastiches based on these incredibly popular motifs. The highly characteristic underdrawing revealed in the infrared reflectogram confirmed the Museum’s attribution to Pieter Brueghel the Younger. This newly discovered masterpiece adds to the Holburne Museum’s outstanding collection of Bruegelian art, which includes ‘Robbing the Bird’s Nest’ and ‘Visit to a Farmhouse’, making it the primary collection of Pieter Brueghel the Younger’s work in the UK.

A book to accompany the exhibition Bruegel: Defining a Dynasty, which includes reflectograms by TSR, is written by Dr. Amy Orrock and published by Philip Wilson, and is now available to purchase.

Links in the Press

Today Programme, Radio 4 http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p04fg153

The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/nov/06/brueghel-family-art-show-holburne-wedding-dancers-centre-stage

The Art Newspaper http://theartnewspaper.com/news/newly-discovered-breughel-to-go-on-show-in-first-uk-exhibition-on-the-dynasty-of-painters/